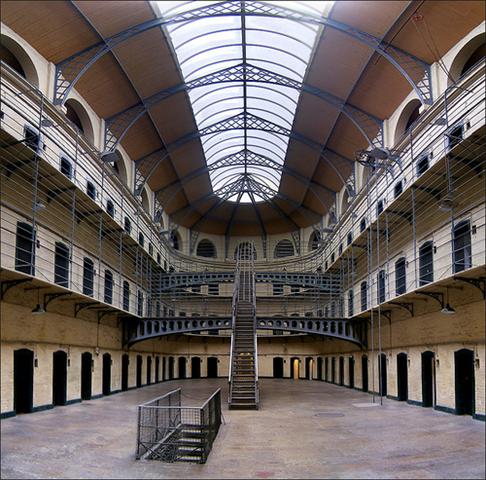

‘The wilderness years’: From Abandonment to Restoration – Kilmainham Gaol 1924 -1960 Kilmainham Gaol, now long established as a national monument, is a unique resource in the study of Irish history. Every year many thousands of visitors make their way to the gaol, most often as a result of the effusive recommendation of inhabitants of the capital city, to absorb something of Irish social, penal and political history in the period from the 1790s to the 1920s. As a result of an inspiring voluntary restoration project, which began in 1960, the gaol was preserved as a monument for future generations, with the motivation for the project being, in particular, that of commemorating the many political prisoners (a virtual role call of the Irish nationalist pantheon) who were imprisoned in the gaol. The gaol is now managed by the Office of Public Works, which had leased the gaol building to the voluntary restoration committee for some twenty-six years (1960-1986). In hindsight one might ask why this restoration work needed to be carried out by a voluntary group at all, why successive Irish governments, in times of greater nationalist feeling, did not instigate or at least actively support or finance such a project. A study of these wilderness years from 1924 to 1960 in fact reveals a remarkable story of governmental inaction, emphasises just how very fortunate it was that the gaol was preserved intact, and illustrates how the present status of the gaol as a national monument owes much to the vision of a virtually unknown Dublin labourer and patriot.

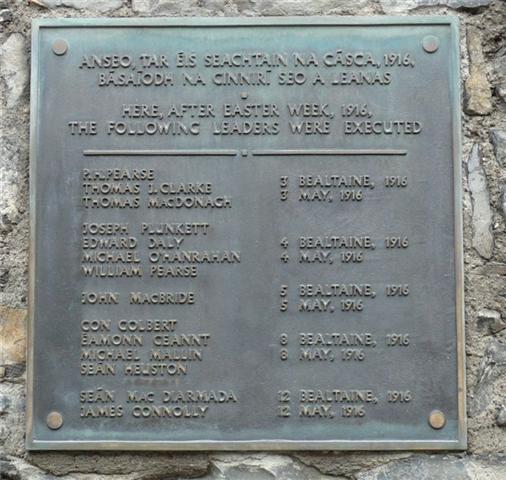

Although the proposal could be considered very insensitive the Prisons Board actually agreed to the request. The offer of the contractors to demolish the west wing of the gaol (the older section) for improved storage space appealed to the Board, who wished to avoid the expense of demolishing it themselves. If Kilmainham Gaol was ever to be used again as a prison the Board had already decided that only the Victorian East Wing would be suitable. Thankfully however, as a later government memorandum recorded, higher authorities discreetly prevailed upon the situation and the contractors request was eventually refused. A statutory order officially closing the premises was made by the Minister of Justice on 1 August 1929, and in accordance with the General Prisons (Ireland) Act 1877, Kilmainham Gaol was automatically transferred to Dublin County Council on the expiration of one year from that date. Almost immediately following this transfer, the county council was to come under pressure over its new acquisition. Letters were received from the National Graves Association (NGA) enquiring as to the council’s intention with the property. The NGA had been formed in 1926 with the declared objective of commemorating all those who died for an Irish Republic. They, therefore, had a keen interest in establishing a permanent commemoration to the patriots executed in Kilmainham Gaol. The attempts by the NGA to secure a memorial at Kilmainham were always spearheaded by Seán Fitzpatrick, the honorary secretary of the association. Fitzpatrick, who worked as a road sweeper for Dublin Corporation in the Kilmainham area, had used his exceptional local knowledge and awareness to assist in organising the renowned escape from the gaol in 1921 of three Volunteers (Ernie O’Malley, Frank Teeling and Simon Donnelly). Living locally, he had always maintained a fascination with the prison. Fitzpatrick now repeatedly wrote to the Council outlining his vision of the gaol as a national monument. He urged the council to consider opening the gaol for visitors during the Eucharistic Congress in the summer of 1932 to highlight Irish patriotic endeavour to both Irish people and to the many foreign visitors. His suggestion was, however, not approved by the council. Later in the year Fitzpatrick wrote to the Minister of Local Government, Sean T. O’Kelly (himself a former prisoner in Kilmainham during the Civil War) requesting that he would receive a deputation from the NGA ‘to discuss the question of permanently marking the place where the men of 1916 and four of the 1922 men were shot, also the enclosing of the place of burial of the men hanged in 1883 [The Invincibles]’. O’Kelly later raised the matter with the president, Eamon de Valera, who appears to have approved of the proposal and it was agreed that the matter would be passed on to the Board of Works for consideration. The first of a number of surveys and estimates on converting the gaol to a museum were carried out, which also involved consultation with the National Museum.

Early proposals by the Board of Works found opposition from the Minister for Education, Tomás Derrig, who expressed the view that the buildings were generally unsuitable for conversion to museum purposes. As an alternative the department put forward a suggestion by the Director of the National Museum, Adolf Mahr, that following the example of Nationalist Spain where the former republican prison in Madrid was preserved as a place of remembrance, the galleries and cells should be retained in their existing state and that memorial tablets should be provided to recall the history of the liberation movements. In other words the gaol would be more a shrine than a museum; there would be no need for any exhibits. This suggestion possibly reflected the national museum’s concerns that their most popular collections, those illustrating Irish political history, would be removed from Kildare Street. Mahr stressed that the gaol premises was unsatisfactory for museum purposes both because of its location and the great expense necessary to convert the gaol adequately for such purposes. Mahr knew the mentality of the department of finance and his emphasis on expenditure probably helped ensure the temporary shelving of the project. Nonetheless, the Fianna Fáil government’s apparent interest in developing the gaol, however lethargic, continued and at a meeting of the executive council on 4 December 1936 it was finally decided that the gaol premises would be acquired by the state from the county council and that the main building would be preserved and the remaining buildings demolished, the site thus obtained being laid out as a public park. Over a year later, however, the gaol building had still not been purchased from the county council. With Seán Fitzpatrick continuing in his efforts to exert pressure on the government the media briefly rallied to his cause. On 14 March 1938 the Irish Press featured a prominent article which included an interview with Fitzpatrick, under the title ‘Shall Kilmainham Fall?’ The article elaborated on Fitzpatrick’s proposal as well as publishing his plans for the treatment of the 1916 plot and the ‘Invincibles’ plot in the form of a memorial park. A special open day, organised by Fitzpatrick and other members of a Seán Heuston Memorial Committee, was permitted by the council on Sunday, 19 March and vast crowds visited the gaol. As the Irish Times recorded: From mid-day to 6pm there was a constant stream of people, and the queue, which waited outside for admission stretched at times to about a quarter of a mile. Over a hundred stewards were on duty to act as guides to the various places of interest, and there was also a large detachment of Civic Guards and members of the St John Ambulance Brigade. Most of the guides obviously had a keen interest in their work. They have studied the history of the prison, and many had vivid stories to tell of escapes, executions and famous men. Later in the same year the gaol and the adjoining land was finally purchased by the Board of Works for the nominal sum of £100. The low price was agreed on the understanding that the prison would be restored as a museum. Following upon the acquisition more estimates and surveys were carried out by the Board of Works, along with further consultation with the National Museum. These deliberations were, however, halted in 1939 following the outbreak of war in Europe. The subsequent Emergency period seemed to allow the gaol museum plans to slide out of focus. In 1945 the Department of Posts and Telegraphs and the Department of Finance both enquired as to the possibility of the gaol premises being adapted for office accommodation. The Commissioner of Public Works advised that such an adaptation could not be carried out at a reasonable cost, and that the premises were, in any event, unsuitable for that purpose. In July 1946 the government decided that the minister for finance would further examine the question of the future of the gaol and ‘should submit to the government proposals for the preservation of the buildings to the maximum extent that might be feasible and desirable, regard being had to considerations of historic interest and to the possibilities of utilising portions of the building for state purposes.’

In August 1953 a cabinet committee meeting decided that the gaol should be converted to a museum with a small memorial park and that with this adaptation no permanent wall or structure would be removed. On 28 August a press release was issued confirming that the government ‘have recently decided that Kilmainham Gaol should be preserved as a national monument, and the necessary steps to that end are being put in place.’ ‘We believe that the spending of money on Constellations [presumably a reference to Aer Lingus’s purchase of a number of Constellation aircraft at this time] and on schemes such as the building of the Bray Road, Kilmainham Gaol, and on new government buildings, should cease. We believe that all these schemes were nonsense and should not have been introduced by Fianna Fáil. I often wonder how deputy de Valera allowed his party to introduce them.’ This kind of depressingly negative mindset (not uncommon in this period) continued to hamper any hopes of progress. Goaded by the remarkable government inaction the baton which had been held for so long by Seán Fitzpatrick was taken up by a Dublin engineer, Lorcan Leonard, who began to gather support for a voluntary restoration project. Leonard was very successful in bringing together a group of concerned citizens (with impressive political clout) to form a provisional restoration committee in 1959. Public meetings were held to outline the proposals for the gaol. An impressive project proposal was submitted to the government by Leonard. At a government meeting on 26 February 1960 the restoration committee’s proposed project was finally approved. Among some of the older government ministers there may have been a measure of relief to have the fate of the gaol settled at no expense. Care of the ‘national shrine’ would be someone else’s responsibility. ‘I am convinced as I always was … out of our poor efforts at least the children of the future will say we preserved the history of Ireland, as far as stone and roofs are concerned, for Kilmainham is the Calvary of republicanism in Ireland. Let them say we gave them neither wealth nor land, but a dream.’ Rory O’Dwyer, a former guide in Kilmainham Gaol, lectures in history at University College Cork Further reading:

|